The Pentland Hills c 1280 AD

(An updated extract of an article written by me for History Scotland Magazine July/August 2005)

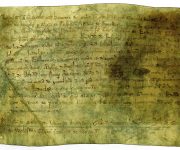

The story of this document is as intriguing and interesting as the story of Harkness itself. Without its survival there would be no record of the origin of the name and one of its earliest holders. The document almost uniquely records the names and locations of ordinary people who were living in an area of Scotland 700 years ago, a time when Wallace and Bruce were children. Its story is closely linked with Scotland’s history and its fight for freedom.

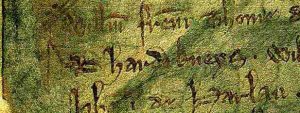

The document is a record of a land inquest or enquiry, held to settle a dispute between farmers living in and around the Pentland Hills about 4 miles south-west of Edinburgh. The dispute arose out of the practice of some farmers to demand ‘punlayn’ – a medieval fine to be paid when animals strayed onto a neighbouring farm. In this case a fine of 8 pence was demanded before animals would be returned. The farms in the area were occupied by tenant farmers. Some of the farms were rented from the king, at that time Alexander III. The King’s farms were mostly in the moor of Pentland, the north and west area of the Hills. The other farmers, the majority, were tenants of the Lord of Brad or Braid who held the lands of Braid and Bavelaw, generally in amongst the Pentland Hills and the areas to the east and south. The jurors in the inquest were drawn from local farmers and land stewards and many of the names survive today in the place names of the area. Since they were ‘quoted as speaking of events “fifty years byfaud [before] or more” it is reasonable to assume that they or their families had long-term associations with the area. One of those jurors named was Thomas de Hardkneys.

The inquest was held in the chapel of St. Katherines of the Hope. There had been a church on this site for centuries and latterly the chapel and its land had been gifted to the monks of Holyrood Abbey, Edinburgh by the Lord of Brad. The chapel, in what is still today a lovely valley in the heart of the hills, now lies under the waters of Glencorse Reservoir, built to supply the demands of a growing Edinburgh in the 1850s. The chapel was the regular place of worship of many of these named and would have been chosen for a meeting place as it was central and common ground to all of those involved. The inquest was recorded on parchment, in medieval Latin, almost certainly by a priest or monk. The Sheriff of Edinburgh at that time had his official base in Edinburgh Castle and the document would have been taken to Edinburgh Castle to be stored along with the other official records of Scotland. “At the end of the thirteenth century, Scotland had a large and well-arranged collection of archives, looked after by a clericus rotulorum, William Dumfries, —” (Scotland from the 11th Century to 1603. Bruce Webster. Edinburgh 1975).

The Road to England

In March 1286 Alexander III died suddenly and tragically when his horse stumbled and he fell over a cliff near Kinghorn in Fife leaving Scotland in astate of chaos. The heir to the throne was Alexander’s infant granddaughter, Margaret ‘Maid of Norway’, who died on the journey to Scotland to claim her throne. A dispute arose between different factions in Scotland claiming the throne. In 1291 Edward I of England, later to become known as ‘The Hammer of the Scots’, was asked to adjudicate and decide which of the claimants should succeed to the throne. Given Edward’s own ambitions to subjugate Scotland, this was a recipe for disaster and was eventually to lead to The Scottish Wars of Independence and a state of conflict between the nations that would continue for centuries. Edward’s first act was to require that all the Scottish documents relating to the succession issue were to be placed in his hands. Many Scottish documents were handed over but there is no reason to believe that the Pentland Inquest document would be amongst them, as it had no bearing on the issue.

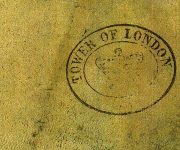

Edward decided the succession issue in favour of John Balliol expecting him to be no more than a puppet through which he could control Scotland. Edward was to be disappointed. In 1296 treaties were signed allying Scotland with France and Norway against England, Edward invaded Scotland meeting little effective resistance. Edinburgh Castle was besieged for eight devastating days before its garrison surrendered. Edward brought sophisticated ‘war engines’ with him capable of throwing enormous stones and balls of lead high in the air and down on the castle, its defenders and contents. The Scottish Records and the Scottish Regalia survived the siege for Edward ordered them to be taken to London. This was part of a calculated attempt by Edward to destroy Scotland’s identity and control its administration. Records such as these are required to resolve disputes over land holdings and questions of precedence. He intended, in future, that decisions would have to be referred to Edward and his successors. Probably removed along in the same baggage train, made up of wooden carts pulled by oxen, were the Scottish Records, the Scottish Regalia; the Black Rood of St. Margaret, Scotland’s holiest relic; and The Stone of Destiny – all taken to the Tower of London. The Records were reputed to have been contained in ‘two leather forcers bound with iron, four hampers covered with black leather, nine wooden forcers, eighteen hampers of wicker and thirty two boxes’. They were joined in the Tower by Scotland’s king, John Balliol, and a number of Scottish nobles. The document was to remain incarcerated in the Tower for 500 years, longer than any of the others. Edward had the Stone of Destiny installed in Westminster Abbey subsequently to be used in the coronations of all English and British monarchs.

The Next 700 Years

There has been much speculation as to what happened next with regard to the Scottish Records. Many believed that Edward had destroyed them. Some recent books dealing with Scottish history state this to be the case. The peace Treaty of Northampton (1328) was supposed by many to have promised their return to Scotland but this did not happen and it was not long before the Scots and English were at war again. For the next 500 years the document recording the inquest in the Pentland Hills lay ‘prisoner/hostage’ in the Tower of London. Many of its contemporaries were destroyed rotting in the dungeons, some eaten by rats. In the mid 1800s an English Public Records Office was set up at Chancery Lane in London. Up until this time English public records had been kept in a variety of locations including the Tower of London. During the transfer process, inventories were drawn up.

In the later 1800s Joseph Bain undertook a monumental task that present day historians still marvel at. He set about the task of recording all the documents and records in the English Public Records Office that had any relevance to Scotland or Scottish affairs. Many of these records were in fact English records that recorded transactions or incidents relating to Scotland or the Scots or between the governments of the two countries. Bain published his findings in a number of volumes between 1881 and 1884 entitled ‘A Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Preserved in the Public Records Office’. Bain noted and précised the document recording the Pentland Hills inquest in Volume IV, addenda 1221 – 1435, paragraph 1762.

The document had been filed in the Chancery file C145/67 along with a number of contemporary 13th century documents from the reign of Edward I. It was described, in the late 1800s by Bain, as being “In bad condition in parts”. Attached to the parchment is a label “Append: Inquis: Edw: I. No.57”. On the back of the document is a ‘Tower of London’ stamp. The other parchments in the file folder appeared to relate to inquests in England. It is a tribute to the thorough and painstaking work of Bain that it was not overlooked. In Volume IV, addenda 1221 – 1435, we find in Bain’s index – “Hardkneys, Thomas of, juror, Bavelay [1280].

Current Situation

In a way we should be grateful to Edward I for removing the document. Given the scale of disruption and destruction that occurred in Scotland during and after the Scottish Wars of Independence, it is doubtful if it would have survived if it had remained in Scotland.

In January 2001 I wrote to George MacKenzie, Keeper of the Records, National Archives of Scotland drawing his attention to this matter. At a subsequent meeting Mr. MacKenzie agreed that the document appeared to be entirely Scottish in content and to raise with the Keeper of the English Records the matter of the return of the document to Scotland. In October 2001 Mr. MacKenzie informed me that the Keeper of the Public Records in England “had responded very positively and, subject to the advice of her Advisory Council on Public Records and the Lord Chancellor, I hope that we can arrange for the return of the document to Scotland”. Mr. MacKenzie pointed out that this could take quite a long time but would keep me informed of progress.

The Stone of Destiny was returned to Scotland in November 1996, almost exactly 700 years after its removal. It is now displayed as part of Scotland’s most precious heritage along with Scotland’s Crown and Regalia in Edinburgh Castle.

The document recording the Pentland Hills Inquest was returned to Scotland in May 2005. (NAS Annual Report pdf 2005/2006 Pages 14/15).

The document is held in the National Archives Scotland – RH 5/231. Information on it is recorded on the People of Medieval Scotland web site.

A fuller account of the Document’s history is contained in my article ‘Edward’s Hostage’ published in History Scotland Magazine July/August 2005.

Extracts of the Document

Bain’s extract:-

“[1280.] August, early in.

1762. Inquisition made in the chapel of Saint Katherine on Friday next after the Feast of Saint Peter ad vincula A.D. 1280 (?) [on the] land of Bavelay by Thomas de Balhernoc, Thomas de Bounayelin, John de Garnhac(?), Gilbert de —–, Robert de Alton, Richard de Harlau, Alan son of Elias, Walter de Balhernoch, John de — and, John de Galwadra, John de Bradwood, Galfrid de Cotis, Henry ‘senescall de Gorth’ (?) —-, William de Walestun, Thomas ‘senescall de Botland’, William brother of Thomas de Balhernoch, Arnald de Listunschelis, Michael ‘senescall de Newt’ (?)- – -, [Thomas] de Hardkneys, William de Harlau, Richard Blauhorne, Alexander de Maleny (?), William de Balin —-, John de Harlau, John Corte, Ranulph Makeles, Thomas Scheipshank, William Wode[man] and Gilbert de Balhernoc, who all sworn and diligently examined, viz., xii of the barony say that for fifty years ‘byefaud’ and more, the K never had right within the bounds of Bavelay, which is the Lord of Brad’s; but the servants of the lords of Brad always took the animals of all the K’s farmers in the moor of Pentland and imparked them, and took ‘punlayn’ whenever they found them within the bounds of Bavelay, and thus all the lords of Brad have ever held that land of Bavelay till the time of Sir William de Sancto Claro and this because Sir Thomas de Brad demanded 8d of ‘punlayn’ from the K’s men, as the K’s men have taken 8d from his men”.

“(Endorsed) Glenrothuan Inviran. S. engual a xl. annis etcetera. [Appendix to Inq. p.m., Edw 1. No. 57.] In bad condition in parts”.

“Indexed: —- Hardkneys, Thomas of, juror, Bavelay [1280] ——“.

Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland. Volume IV, 1357 – 1509: addenda 1221 – 1435: para. 1762. (Edinburgh 1888).

*********

Many of the names of jurors at the inquisition can still be recognised in farms and villages that exist in the Pentland Hills today:-

| Balhernoc | Balerno |

| Bounayelin | Bonally |

| Botland | Buteland |

| Harlau | Harelaw |

| Bradwod | Braidwood |

| Cotis | Coates |

| Walstun | Walstone |

| Maleny | Malleny |

| Listunschelis | Listonshiels |

**********

Public Records Office précis of the document:-

2039. Inquisition in the chapel of St. Katherine. Friday after St. Peter’s Chains —–.

“Fifty years past and more the king never had right within the metes of Bavelay, which belongs to the Lord of Brad, but always the servants of the lords of Brad took the animals of all the king’s farmers in the moor of Pentland and impounded them, and took punlayn, when they found them within the metes of Bavelay, and thus always the lords of Brad held that land of Bavelay until the time of Sir William de Sancto Claro, and this because Sir Thomas de Brad sought 8d of punlayn of the king’s men as the king’s men took 8d of his men”.

C. Inq. Misc. File 67 (3)

Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous (Chancery) 1219 – 1307. Preserved in the Public Records Office. Published HMSO 1916